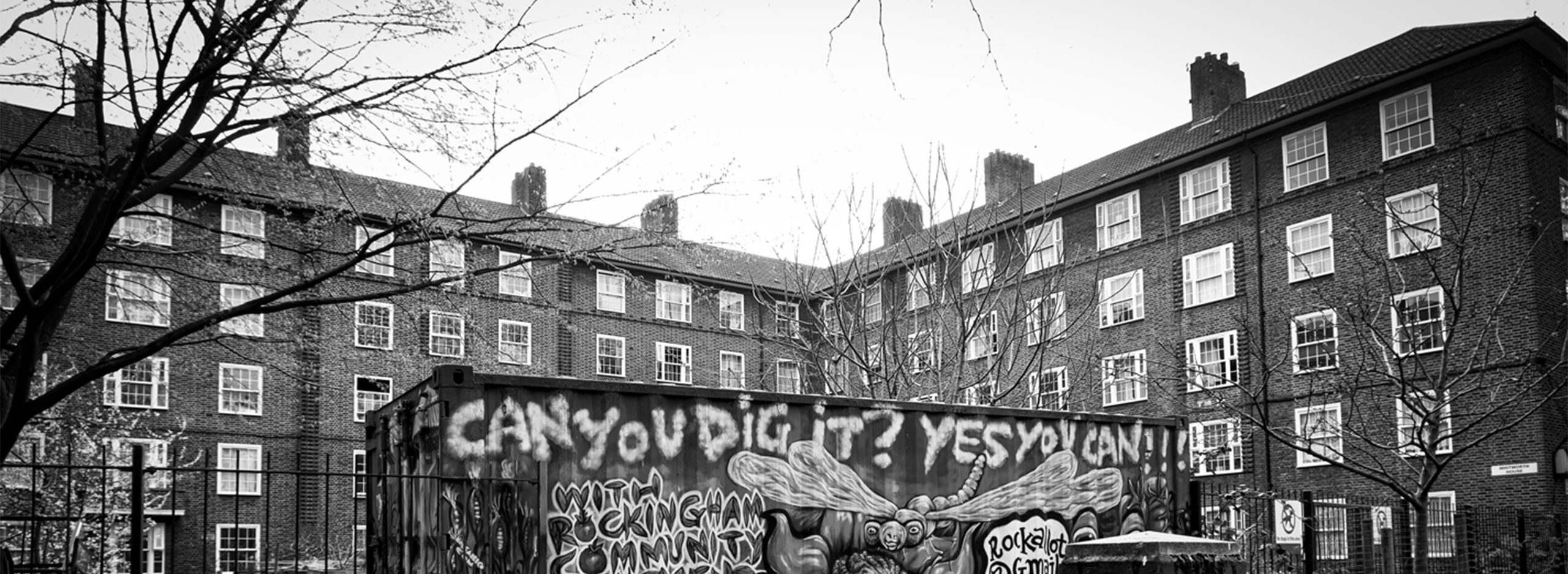

After the EU referendum in 2016, with support from the Friends Provident Foundation, I started travelling around the UK with my camera and a notebook, asking people why they voted for Brexit. I documented how these people were coping with cuts. In the last three years I have written hundreds of interviews and stories about communities forced to step in as the state has retreated, from a supermarket that gives away food waste to the hungry, to fishermen who bought their harbour, to young people building their own homes. I discovered that an unequal system was taking its toll on the most vulnerable.

But I didn’t expect to find a similar sentiment when I moved to Dresden in October 2018. I applied to the International Journalists’ Programme, a charity that gives young journalists the chance to work abroad as correspondents for a couple of months. They offered me a placement working at Sächsische Zeitung, a daily newspaper based in Dresden, East Germany. The paper serves whole of Saxony and has a daily circulation of 230,000 – almost double that of the Guardian.

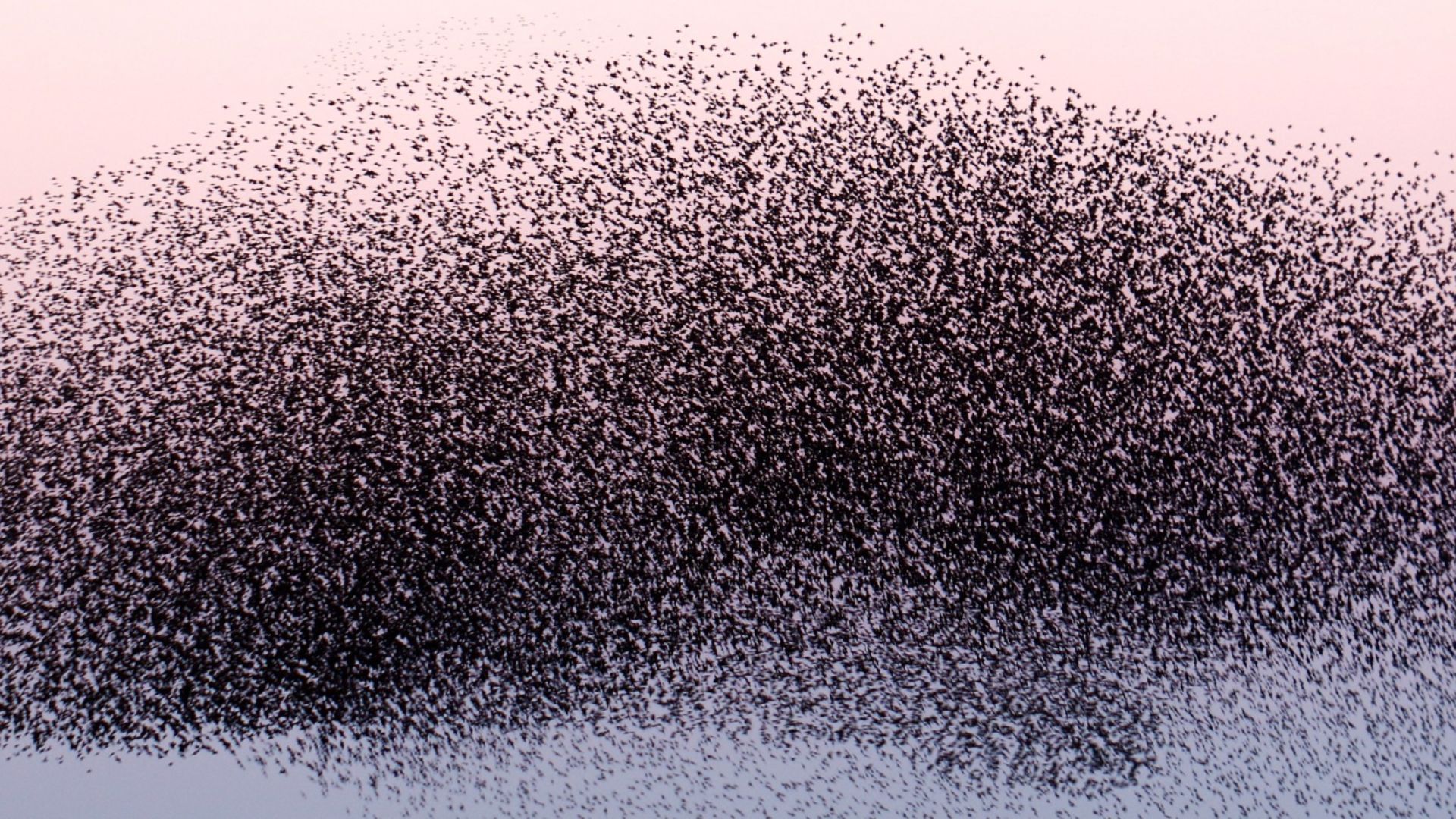

On my first week on the politics desk, two reporters asked if I would like to attend the weekly rally in the Altmarkt held by PEGIDA, a nationalist, anti-Islamic organisation that started in Dresden in 2014. Every week for more than four years, someone from Sächsische Zeitung has gone to bear witness to the movement.

That night, I kept close to the reporter on duty. We approached the Altmarkt, Dresden’s old market square, on foot to the rousing strings of Together We’re Strong, the PEGIDA hymn. In the square, armed police stood in a no-man’s-land between counter-protesters and the PEGIDA demonstration. My colleague nodded a greeting at the police chief as we passed. Both had been coming here a long time. It wasn’t unheard of for there to be violence against journalists on the beat.

I tried to film discreetly: the woollen hats in the colours of the German flag, the home-made banners, the older couples that had come out in the cold to hear Lutz Bachmann, the founder of PEGIDA, deliver his hate speech against Muslims. I heard a handful of references: a celebration of the election of Jair Bolsonaro, a slur against Chancellor Angela Merkel’s open borders, a promise that the UK would be better off out of the EU.

Surrounded by supporters, I no longer felt shocked. These grey-haired people with their patriotic hats seemed familiar. They were my neighbours from my Brexit-voting hometown of Peterborough in England, who casually used racial slurs to refer to the Pakistani families who owned the corner shops. They were my older relatives, who felt their way of life was under threat from helpless immigrants drowning on boats miles away in the Mediterranean.

Fear unites the right. During my time in Dresden, I learned that East Germans are still paid less than their counterparts in the West. When the Berlin Wall fell, many West Germans moved to east to buy up businesses and property, making East Germans second class citizens on their own land. East Germans fear poverty in retirement, because they own so little private property, having always relied on the state. These people would have voted for Brexit. They were already cheering it on at rallies.

Immigrants are the victims of this fear. Dresden is extraordinarily white and monocultural compared to London. Yet people with no experience of the other were voting to “shut the gate” to refugees and making scapegoats of immigrants. Brexit voters, PEGIDA supporters: they do not fear immigrants so much as the notion of losing out even more in a system that was already rigged against them.

Every time I interviewed someone on my travels in the UK, I asked why they voted for Brexit. Fishermen told me they couldn’t make a living because of European fishing policies. A young man was afraid that immigrants were taking jobs. One young women hoped that house prices would crash after Brexit, so she could afford to buy a home.

Their answers reflect the fear of being left behind by a system fuelled by inequality. Brexit voters and PEGIDA marchers have both turned to extreme political views espoused by people who promise to act on their fears. This process happens quietly in countries where elites control the governments and the media and only certain types of people are able to make their voices heard. It isn’t until elections when the results are written loudly in the numbers of people turning against the established systems.

Meanwhile the middle-ground is frozen. Mainstream politicians, bamboozled by current affairs, fail take action to close the gap between rich and poor. Germany and the UK are two of the largest economies in the world. For any such government to inflict policies that lead to hunger and homelessness is political choice, not economic necessity. Not only do these nations have the resources to support migrants, but they need workers from outside to keep the engines of their economies burning as the native population ages.

The task is to integrate newcomers while giving those who feel excluded the rights and means to help themselves. We must send a new message: not that we live in a time of scarcity, but that we have enough.